REPENTANCE

by George Herbert

Lord, I confesse my sinne is great;

Great is my sinne. Oh! gently treat

With thy quick flow’r, thy momentanie bloom;

Whose life still pressing

Is one undressing,

A steadie aiming at a tombe.

Man’s age is two houres work, or three:

Each day doth round about us see.

Thus are we to delights: but we are all

To sorrows old,

If like be told

From what life feeleth, Adam’s fall.

O let thy height of mercie then

Compassionate short-breathed men.

Cut me not off for my most foul transgression:

I do confesse

My foolishnesse;

My God, accept of my confession.

Sweeten at length this bitter bowl,

Which thou hast pour’d into my soul;

Thy wormwood turn to health, windes to fair weather:

For if thou stay,

I and this day,

As we did rise, we die together.

When thou for sinne rebukest man,

Forthwith he waxeth wo and wan:

Bitternesse fills our bowels; all our hearts

Pine, and decay,

And drop away,

And carrie with them th’ other parts.

But thou wilt sinne and grief destroy;

That so the broken bones may joy,

And tune together in a well-set song,

Full of his praises,

Who dead men raises.

Fractures well cur’d make us more strong.

iserere me, Domine—“Have mercy on me, O Lord”; that’s the 51st psalm. If you pray the traditional Liturgy of the Hours, you pray it every morning at Lauds. You begin every day with repentance, as you begin every Mass with repentance. “Have mercy on me, O Lord, for I have sinned.” It is good for those to be the first words you say each day. In that spirit George Herbert begins his poem: “Lord, I confesse my sinne is great.” Before a Catholic becomes a full member of the Church, the first thing he or she does is go to Confession. Repentance is first; the Church’s readings for the first Sunday of Lent, Year A—the first of the three-year cycle—begin with the reminder that we all have sinned in Adam. Repentance is first.

For Christ, who is like us in all things but sin, obedience is first. No sooner do we come into the Church than we go home and sin, but when Christ was baptized, the first thing he did was go into the wilderness and resist the temptations of Satan. And so in the readings at Mass the Church reminds us of our own sinfulness, and of Christ’s obedience. Just as through the disobedience of the one man, many were made sinners, so through the obedience of one, many will be made righteous.

It is not our obedience that heals us, but Christ’s obedience.

•••

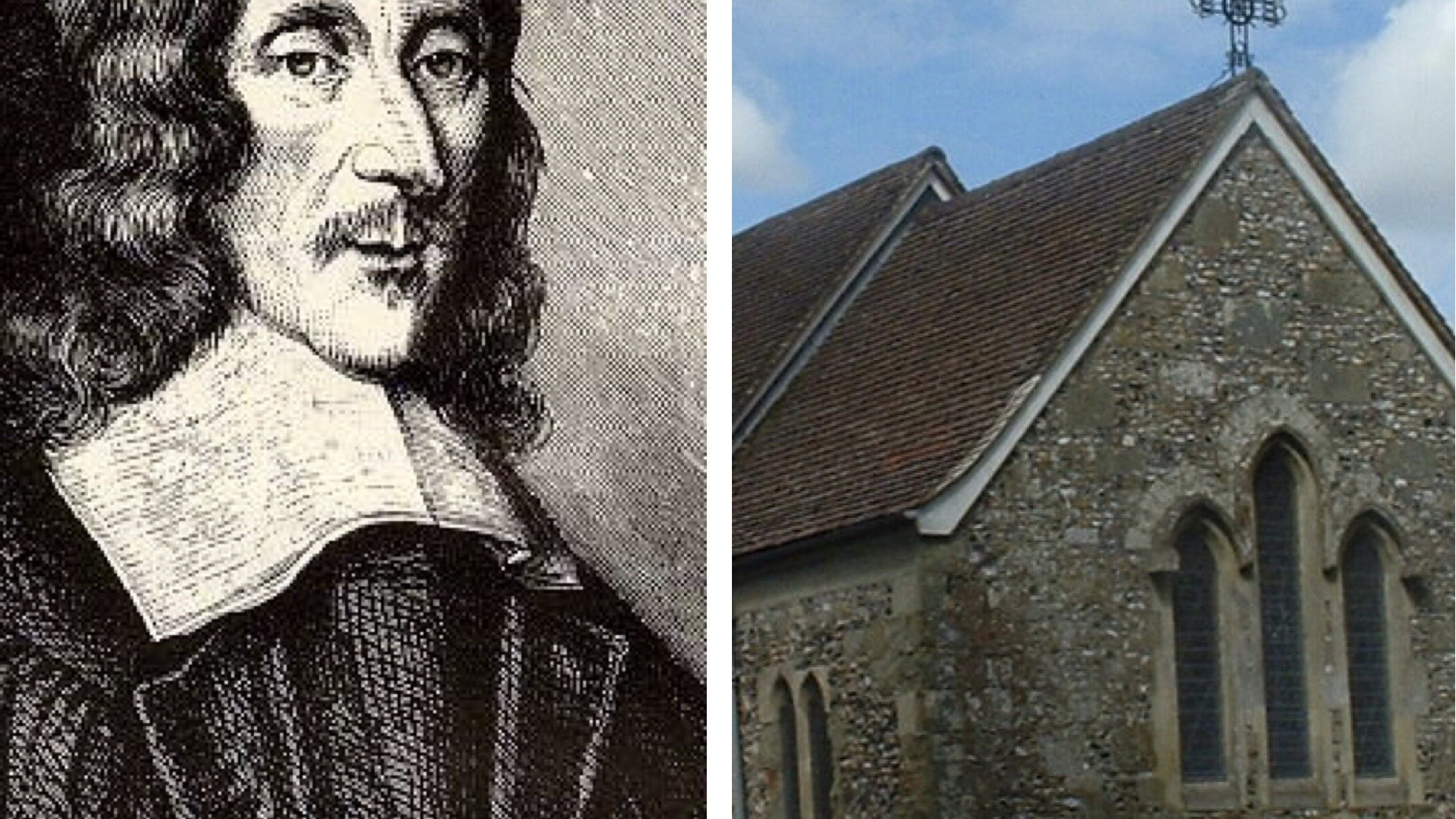

George Herbert, a contemporary of John Donne and fellow devotional poet and Metaphysical poet, was also an Anglican priest. Born in Wales in 1593, but raised in England, he attended Trinity College and for a brief time, during the reign of King James I, was a member of Parliament. In 1630, he was appointed rector of St. Andrew’s in Wiltshire, where he remained until he died just three years later, of consumption, at the age of 39.

“Repentance”—which is Herbert’s 51st psalm, his Miserere—first appeared in the collection The Temple. You can find it at the Internet Archive. Shortly before his death, Herbert sent the manuscript to Nicholas Ferrar; Ferrar published it later the same year. The Temple is subtitled “Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations.” (An “ejaculatory prayer” is a short prayer prayed to God in an emergency; for example, “Lord Jesus, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”)

•••

Herbert begins the right way, by confessing sin; and his sin is so great that he has to mention it twice in the first sentence: “Lord, I confess my sinne is great; / Great is my sinne.” Repetition is never accidental. This particular repetition is a chiasmus; the word literally means “crossing.” Specifically, it refers to the crossing of strokes in the letter X (chi in Greek). The letter X reads the same backward and forward, and a chiasmus is repetition in reverse order: “Lord, I confesse [a] my sinne [b] is great; / [b] Great is [a] my sinne.”

So great is it that Christ alone is the remedy. “[G]ently treat / With thy quick flow’r,” Herbert prays. (“Flower” is a reference to Christ.) It amuses me that Herbert wants his sin to be treated “gently.” Heal me, Lord, but please do it gently! It is human of Herbert to want an easy cure, though we’ll soon learn—as will he—that his sin can have no “gentle” remedy. The point he resists, and doesn’t get to until the last line of the poem, is that his sin should be well cured.

Christ’s life, Herbert tells us is “one undressing / A steadie aiming at a tombe.” Christ came to be stripped naked (“one undressing”) and killed at Calvary; that was the point; everything he did had that as the single end. Our redemption cost God. It did not come gently for the Savior. Why should Herbert expect it to come gently for himself?

Christ’s life, like Lent itself a “steadie aiming at a tomb,” reminds Herbert that his own life is brief: “Man’s age is two houres work, or three.” Herbert, who was always sickly, was certainly conscious of his own death. Probably he knew his “houres” were nearer two than three. The “delights” of those “houres” are tempered by “sorrows old”—that is to say, original sin, inherited by “Adam’s fall.” Our life is brief—“two houres work, or three”—because death came into the world by sin.

The shortness of life reminds Herbert to ask God again for compassion and gentleness: “O let thy height of mercie then / Compassionate short-breathed men.” (“Breathed” is two syllables, and “compassionate” is a verb: you pronounce it com-PASH-un-EIGHT.) “I do confesse / My foolishnesse,” Herbert says, as though this additional repetition will convince God to let him off easy.

In the next stanza, Herbert is still asking for gentleness, but he realizes that it’s not going to be as easy as he may have hoped. “Sweeten at length this bitter bowl / Which thou hast pour’d into my soul.” To be healed from sin requires “bitter” remedy—a pouring of “wormwood” into the soul—and Herbert’s hope now is for sweetness “at length.”

The sweetness is not in the cure, but in the holiness you have after the cure. “Thy wormwood,” Herbert prays, “turn to health.” God’s purpose, Herbert realizes at the end, is to “destroy” our “sinne and grief,” and that requires a “bitter” remedy. Quoting Psalm 51, Herbert writes: “Thou wilt sinne and grief destroy; / That so the broken bones may joy.”

God’s purpose is not to heal us gently but to heal us well. A pat on the head doesn’t make us holy when our sins are so grave we have to mention them twice in the first sentence. Fractures well cured make us more strong.

Discover more from To Give a Defense

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.