hen the Protestant apologist Walter Martin debated infamous atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair on a radio show in 1968, he declared: “First we’re going to talk about language.” He was calling out her equivocation on key terms and trying to get her to admit that “in certain contexts, words always mean the same thing.” O’Hair never did admit it, but that was a priceless line: “First we’re going to talk about language.”

This post is the first in a series on papal infallibility; and because infallibility is so widely misunderstood—even by Catholic standards of misunderstanding—we’re going to talk first about how the Church defines it. That’s the only way to have a reasoned discussion about heresy, about apostasy, about schism, and it’s the only way to have one about infallibility.

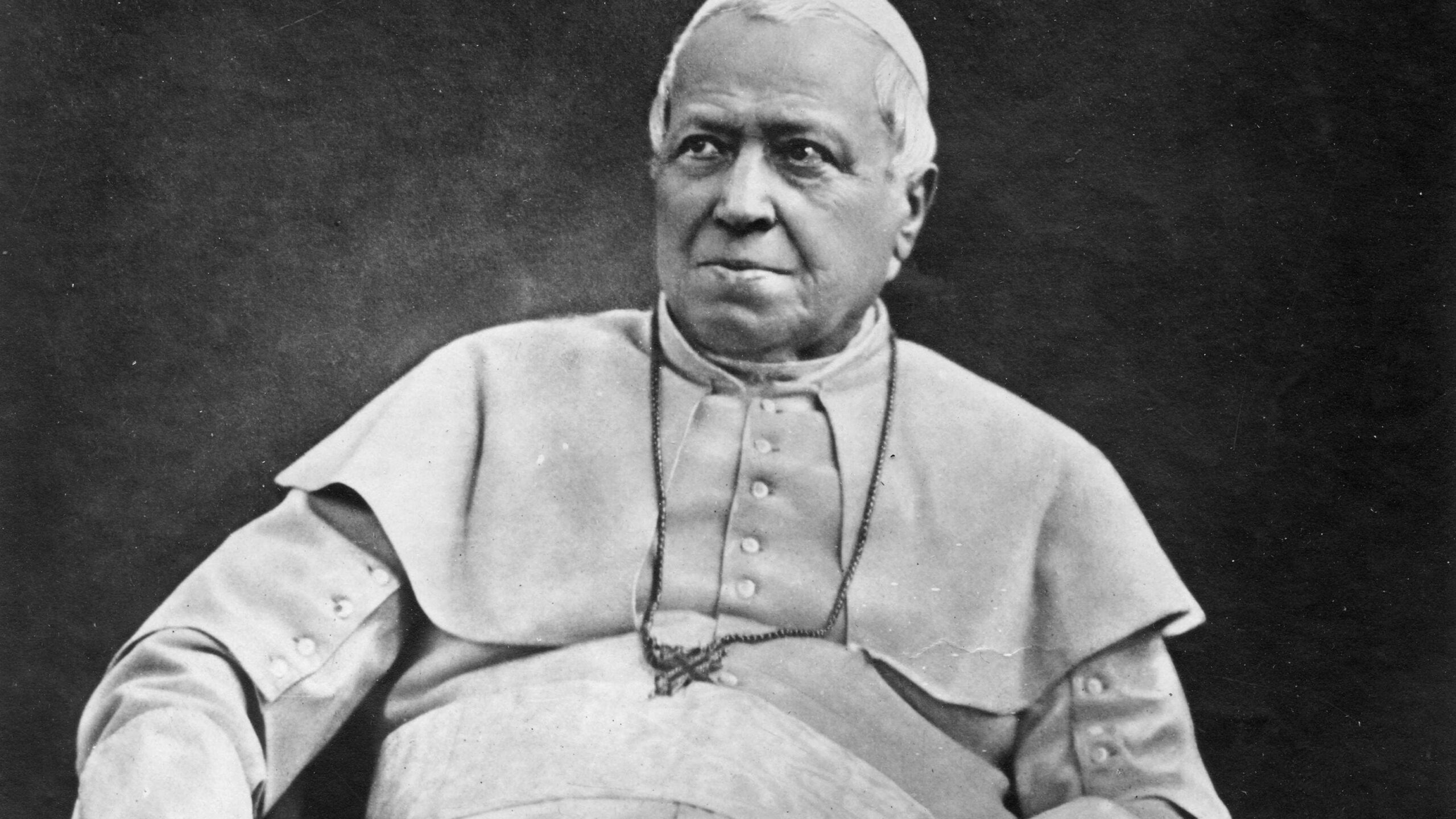

The Church formally defines this dogma at the First Vatican Council, in the document Pastor Aeternus (July 18, 1870).

A DIGRESSION ON “DOCTRINE” AND “DOGMA.”

A brief parenthesis is in order, however, before we open those heavy conciliar tomes. Infallibility is a dogma, and some people get hung up on what a “dogma” is and how it differs from a “doctrine.” Simply put, a dogma is a truth the Church understands to have been revealed by God. A doctrine, though the Church teaches it with authority, is not divine revelation.

So for example, it is divine revelation that Jesus is God (specifically, the Second Person of the Trinity): That’s a dogma. But the Church’s stricture on contraception is not divine revelation: That’s a doctrine. You can find the definition in the Catechism §88. These words get mixed up all the time, but it’s important to use them correctly.

DISSECTING A DEFINITION.

That out of the way, we can fling dust in the air and consult the fusty texts of Vatican I to find the official definition of infallibility:

We teach and define that it is [1.] a divinely-revealed dogma: [2.] that the Roman Pontiff, [3.] when [4.] he speaks ex Cathedra, that is, when in discharge of the office of Pastor and Teacher of all Christians, by virtue of his supreme Apostolic authority, he [5.] defines a doctrine regarding faith or morals [6.] to be held by the Universal Church, [7.] by the divine assistance promised to him in blessed Peter, is possessed of that infallibility with which the divine Redeemer willed that His Church should be endowed for defining doctrine regarding faith or morals: and that therefore [8.] such definitions of the Roman Pontiff are irreformable of themselves, and not from the consent of the Church.

Thus in a single serpentine sentence, the Church defines infallibility. I am always amused by people who complain about the murky jargon coming out of the Vatican today, as though a sentence like the one above is plain and clear. But no. We have no choice but to face this reptile and dissect it scale by scale.

- Infallibility is a dogma: It has been revealed by God.

Many people dispute this; even Catholics dispute this. I don’t dispute it—I will defend it later in the series—but for now I merely point out only that that’s how the Church classifies its authority. It’s a dogma; it’s divine revelation. Catholics are obligated to accept this teaching; to dispute it would be at least material heresy. My only gripe with the expression “divinely-revealed dogma” is that it’s redundant. There are no other kinds of dogmas cluttering up Church teaching; for which we can be grateful.

- The definition in Vatican I applies exclusively to the pope.

Some wrongly think that Vatican II extended infallibility to the other bishops, but that is not what Lumen Gentium 25 says. “[T]he individual bishops,” it says, “do not enjoy the prerogative of infallibility.” Bishops teach infallibly only when they are (1) “in agreement on one position” and (2) they teach in union with the pope. They have no independent charism of infallibility. Bishop Crankberg of the Diocese of Independence can’t act on his own and define Mary to be co-redemptrix. Only Pope Francis or another successor of Peter can do that.

A second point (I will develop this more in a later post) is that ecumenical councils and Sacred Scripture are also infallible—with these caveats: (1) Ecumenical councils must be affirmed by the pope before they have an authority whatever; (2) the Church is the only infallible interpreter of Sacred Scripture. This is a much more complicated subject than a paragraph can convey, and I will set it to the side for now. For now it’s enough to point out that Pastor Aeternus restricts infallibility to the pope.

- There are limits to the pope’s exercise of infallibility.

Words matter, and here I get a whole bullet point out of the single word “when.” The pope has infallibility, according to Pastor Aeternus, “when.” Not everything a pope says is infallible.

(Incidentally, some of my critics—those who falsely accuse me of “papolatry” and “ultramontanism”—seem to think my position is that everything a pope says is infallible. That is false. I’ve never said that, never believed that, have always said the exact opposite, and repeat it now: Not. Everything. A. Pope. Says. Is. Infallible. Time and again I correct my critics, but they never retract their false accusations. So it goes.)

Anyway, most of what the pope says isn’t infallible. If Pope Francis wakes up tomorrow morning and complains, “My breakfast is cold,” it’s possible his breakfast is hot. If Pope Francis says in an interview (as he has) that Luther “did not err,” he is manifestly wrong.

- To be infallible, the pope must speak ex cathedra.

Ex cathedra is Latin for “from the chair.” A chair is a symbol of authority. From “cathedra” we get the word “cathedral”; a cathedral is where the local bishop’s “chair” is. Pastor Aeternus has a very wordy explanation for what it means for a pope to speak ex cathedra (because it has a very wordy explanation for everything). A pope speaks ex cathedra “when in discharge of the office of Pastor and Teacher of all Christians, by virtue of his supreme Apostolic authority.”

I can make all that simpler: To be infallible, the pope has to be expressly acting as teacher of the whole Church.

An example of this kind of thing (a controversial one, I know, but I cite it anyway) is Ordinatio Sacerdotalis. In this document, Pope St. John Paul II reiterates the teaching that the priesthood is limited to men. In the penultimate paragraph, the pope specifies that he is writing “in virtue of my ministry of confirming the brethren.” He cites Luke 22:32—not coincidentally, the same text that Pastor Aeternus cites to lend biblical support to the dogma of infallibility.

- To be infallible, the pope must define “a doctrine regarding faith or morals.”

Note the use of the word “doctrine” here. It is not just dogmas, but also doctrines, that can be infallible. Doctrines are not divine revelation like dogmas are, but if the pope solemnly defines them, they are still infallible.

It helps to think of it this way: All dogmas are infallible; not all infallible statements are dogmas. All divine revelation is infallible; not all infallible statements are divine revelation. It’s not always divine revelation that a pope is defining, though in the case of infallibility it is.

You may ask: “But Alt! How do I know when the pope has “defined” something?”

Usually, you know because the pope uses the word “define.” For example, in Munificentissimus Deus (1950), Pope Pius XII teaches the Assumption of Mary in these words:

[W]e pronounce, declare, and define it to be a divinely revealed dogma: that the Immaculate Mother of God, the ever Virgin Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory.

Like most things in Catholic theology, it’s a lot more complicated than that: John Paul II does not use the word “define” in Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, only the word “declare.” But we can leave it at that for now.

- To be infallible, the pope must define a dogma (or doctrine) “to be held by the Universal Church.”

You’ll find that kind of language in Ordinatio Sacerdotalis. John Paul II writes: “[T]his judgment [i.e., the priesthood is reserved to men] is to be definitively held by all the Church’s faithful.”

You will also find it in Munificentissimus Deus: “Hence if anyone, which God forbid, should dare willfully to deny or to call into doubt that which we have defined, let him know that he has fallen away completely from the divine and Catholic Faith.”

Often, particularly in ecumenical councils, the Church pronounces an anathema on anyone who denies some particular dogma of the faith. An “anathema” does not mean, as some falsely think, that a person has been condemned to Hell. It’s an excommunication—an especially grievous excommunication in which you’re excluded from the Church altogether, traditionally with bell, book, and candle. Lesser excommunications exclude you from the sacraments; only an anathema excludes you from the Church.

(Did you know where that expression—“bell, book, and candle”—comes from? During said grievous excommunication, the bishop would ring a bell, close a holy book, and snuff a candle—usually by dashing it to the ground in a liturgically authorized fit of offended righteousness. But I digress.)

- The pope enjoys infallibility “by the divine assistance promised to him in blessed Peter.”

The pope has infallibility because he enjoys “divine assistance,” not because he enjoys some superhuman personal quality. He has divine assistance in defining truths of the faith in the same way that the authors of the Bible had divine assistance in writing their respective books.

- Because the pope has divine assistance, infallible teachings are “irreformable.”

They are irreformable, says Pastor Aeternus “of themselves, and not from the consent of the Church.”

Sensus fidelium (“the sense of the faithful”) is a term in Catholic theology that refers to teachings the Church considers true by virtue of “universal consent”: This is what all Catholics believe. But what Pastor Aeternus tells us is that sensus fidelium has no bearing on infallible teachings. Because the pope had divine assistance in arriving at these definitions, it doesn’t matter how many of the faithful agree or disagree. Of themselves (i.e., being infallible) they are “irreformable.” They are irreformable as Sacred Scripture is irreformable. Sensus fidelium can’t change John 14:6, or any other verse of Scripture, and it can’t change the infallible definitions of the pope.

INFALLIBLE TEACHING VS. PAPAL OPINION.

Vatican I gives us a limited definition, and we must understand those limits. A teaching is not infallible just because the pope said it, but because the pope said it in a very specific context. John Paul II’s Ordinatio Sacerdotalis is infallible, but the article he wrote for Osservatore Romano calling St. Maria Goretti a martyr to chastity is just an opinion. If we’re going to think clearly, we must make distinctions. The purpose of this post—the first in a series—was to help us start to make those distinctions.

Discover more from To Give a Defense

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.