r. Bill McCormick asks the question in connection with a discussion that arose after two articles by Massimo Faggioli in La Croix International. If you are interested, you can read these articles here. Michael Sean Winters had a response at the National Catholic Reporter and Pedro Gabriel at Where Peter Is. That’s just the background; Dr. Faggioli is a Facebook friend of mine, thinks the America article misrepresents his argument, and I don’t wish to wade into that dispute. I haven’t read any of these articles yet, and can’t speak for them. My purpose is just to add a few footnotes where I think Fr. McCormick gets the answer to his question exactly right.

The article begins:

Massimo Faggioli has created a stir with his provocative articles in La Croix about the limits and failures of Pope Francis’ pontificate. But Mr. Faggioli’s deepest concern has gone unanswered and, indeed, unnoticed by most commentators. I am grateful to Mr. Faggioli for his input, but the question he implicitly raises remains: What happens when Pope Francis disappoints his supporters?

Well, often they wail like jilted lovers (as I’ve noted before). Good heavens, the pope is Catholic. We expected so much more! How can this be? How can I go on? But it bothers me, this idea that the pope has “supporters.” He’s not a political candidate, and Catholics aren’t supposed to divide themselves into factions who are either “supporters” or “opponents” of the Holy Father. The pope isn’t supposed to have a base; he’s supposed to have children.

This sense of betrayal [among the pope’s so-called “supporters”] matters for many reasons. Among other things, it parallels how some critics of Francis assess the pontificate. Among a few prominent U.S. Catholics, the support shown for the papacy under popes St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI turned out to be conditional after 2013.

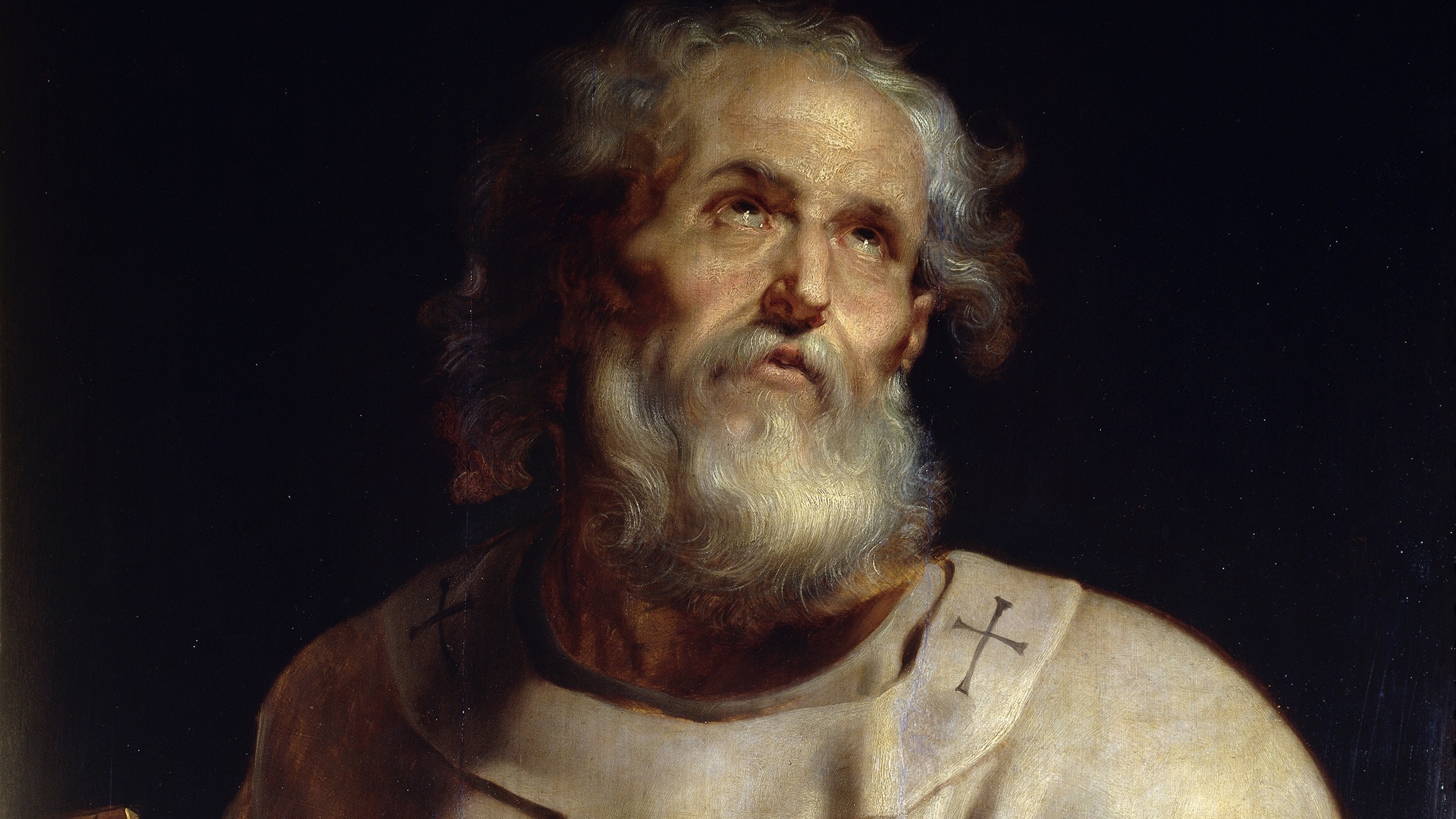

And it’s not supposed to be “conditional.” You must not give the pope “support” or withhold it, based on whether or not he’s “your guy” or enacts “policies” you favor. My critics often entertain the idea that, once Francis is no longer pope—replaced by Cardinal Sarah maybe—I’ll withdraw my defenses of Peter. I’ll develop Pope Pius XIII Derangement Syndrome (or whatever name Sarah would take in that case). But no. Even if Cardinal Burke were to become the pope and take the name Boniface X, hic est Petrus. My allegiance to the pope has no condition. Whether his name be Joseph Ratzinger, or Jorge Bergoglio, or Raymond Burke, or James Martin, he sits in Peter’s chair. That’s the only condition that matters.

A vocal minority is still a minority, but it has become easy to forget that there are also people of good faith with genuine concerns and questions about Francis’ papacy. [No doubt. I know many such.] There are also many Catholics of good faith who disagree with some of the policy prescriptions for which Mr. Faggioli advocates. What faces the U.S. church is a growing sense that the pope is a political official one supports when he favors your agenda or at least when he has the same enemies.

Yes; if you’re looking for the pope to enact items on some particular agenda you entertain, you’re likely to be disappointed. The pope’s a father; he’s a shepherd. He’s not your own personal Santa Claus. For example, I don’t happen to think there’s anything amiss about a female diaconate, as long as no one thinks this constitutes sacramental “ordination.” But the laity aren’t supposed to be lobbyists; if the pope decides against it, fair enough. There’s no reason to compose a dirge over it.

This is what I see as the trouble with much day-to-day analysis of the papacy. The rise of the global papacy, 24-hour news, the internet, social media and so on has trained us to bet our cards on change, novelty and movement. It keeps us hungry and impatient for still more change. But it is not good at cultivating our attention on what is enduring, what continues and sustains us across pontificates.

It is indeed bothersome to constantly have papal actions and utterances ground up and distorted by the news cycle. I’m not sure what to do about it. But a lot of what I have tried to do on this blog is to show how Pope Francis’s words are entirely consistent with those of Benedict XVI, John Paul II, the Catechism, Vatican II, the Church Fathers, and the Bible. The regrettable existence of Pope Francis Derangement Syndrome has given me an opportunity to examine the pope’s words very carefully, and I have repeatedly been struck by how similar the pope is to his predecessors. It reassures me in my Catholic faith—that the teaching office of Church is indeed protected by the Holy Spirit. Pope Francis speaks within a consistent tradition. There’s not much at all, I have found, that is novel. That’s a good.

The desire for the pope to enact a particular agenda, Fr. McCormick concudes, deprives Catholics of an opportunity to “focus on what unites the church. Rather, it emphasizes division and conflict.”

If my real desire was that the pope be “my guy,” then I would have spent the last 7 years disappointed. To be (excuse the pun) frank, Pope Francis has never been “my guy.” I would have preferred someone much more similar to Pope Benedict XVI. I wanted Cardinal Scola to succeed him. I don’t mean that Pope Francis is a contradiction to Pope Benedict, only that different popes have different emphases, and Pope Francis’s have never really been my own.

But that’s the very reason I needed a Bergoglio in Peter’s chair. Pope Francis has kept me from isolating myself in some narrow corner of Church teaching and has reminded me of the importance of truths that I tended to neglect. The next pope will, by God’s grace, have his own emphases. And thus, many papacies keep the Church in balance.

That’s why we are to be sons and daughters, not partisans. Having an allegiance to the pope, whoever he is—Ratzinger today, but Bergoglio tomorrow and maybe Sarah next year—is a check upon Catholics isolating themselves into a bunch of different factions. Factions hurt Church unity.

My two cents.

Discover more from To Give a Defense

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.